It is almost a truism that we, ourselves, are our own worst enemies when it comes to understanding ourselves and thinking clearly. Without investigating the pioneering psychoanalytical work of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, I would like to take a simple model of a conscious/unconscious mind and see how that might help us understand ourselves a little better and help us think more clearly.

Why we do things is often quite mysterious. I want to explore how accessing the less accessible parts of our minds and personality enable us to think more clearly and make decisions that are more in tune with our whole personality rather than based on purely rational factors.

Let’s look at some history of the idea of “outside influencers” within the human mind, some modern examples of the shadow self and how this might work in practice when it comes to making decisions and sticking to them.

The idea of outside influencers on thinking and motivation

First, some background. The term “unconscious mind” was coined by the 18th-century, German romantic philosopher Friedrich Schelling and later introduced into English by the poet and essayist Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Influences on thinking that originate from outside of an individual’s consciousness were reflected in ancient ideas of temptation, divine inspiration and the predominant role of the gods in affecting motives and actions. Unconscious aspects of mentality were referred to between 2,500 and 600 BC in the Hindu texts known as the Vedas, the basis of Ayurvedic medicine.

In the Hellenistic ruler cult that began with Alexander the Great, it was not the ruler but his guiding daemon that was venerated. In the early Classical Period, the idea of an individual daemon had been expanded from the aristocracy to the ordinary citizen and was accepted as normal for each citizen for whom it served to guide, motivate and inspire.

Socrates, for instance, believed he had a daemon that would warn him of the consequences of his actions and that served as a spirit guide or conscience to lead him through his life. Daemons, in the Greek tradition, were demigods and their ability was akin to a second sight.

Similarly, the first-century Roman imperial cult began by venerating the genius or numen of Emperor Augustus, the unconscious spirit which guided his courage, statesmanlike qualities and wisdom.

In Western thought, Paracelsus is credited as the first to make mention of an unconscious aspect of cognition in his work Von den Krankheiten (“About illnesses”, 1567) and his clinical methodology created a system that is regarded by some as the beginning of modern scientific psychology.

Shakespeare explored the role of the unconscious in many of his plays, without naming it as such. Hamlet’s famous soliloquy is, arguably, a conversation with his unconscious demons or daemon.

Western philosophers from Spinoza to Nietzsche developed a western model of the mind which foreshadowed Freud’s theories of the id, superego and ego. It is difficult to find a nineteenth-century psychologist or psychiatrist who did not recognise the unconscious as not only real but of the highest importance in human motivation.

As psychoanalyst Carl Jung observed: “The shadow is the negative side of the personality, the sum of all those unpleasant qualities we like to hide, together with the insufficiently-developed functions and the contents of the personal unconscious… [the shadow] also displays a number of good qualities such as normal instincts, appropriate reactions, realistic insights, creative impulses“.

Modern examples: David Richo

A modern psychotherapist, David Richo, believes that a shadow self –the Jungian dark side of the personality – is hidden in the psyche. Others often recognise our shadow in us through our behaviour but, often, we do not.

Richo has written a practical guide, Shadow Dance, in which he introduces the reader to the conscious persona and the subconscious shadow. He includes conscious, but negatively-perceived traits, in his definition of the personality’s dark side, plus undiscovered or unused positive traits. By helping the reader to come to terms with and befriend the shadow self, instead of projecting it onto others in dysfunctional or destructive ways, the author points the way towards a personal development path, freeing emotional and creative resources through which we can manifest brighter, healthier lives.

Befriending the shadow makes fear an ally and enables us to live more authentically. It also automatically improves our interpersonal relationships because we are freed from the need to project our own negativity onto others and we become more acutely aware when theirs is projected onto us.

Modern examples: Philip Pullman

Jung’s and Richo’s shadow bears some resemblance to Philip Pullman’s daemon in his trilogy of fantasy novels, His Dark Materials (taken from a quotation from seventeenth-century poet John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Book 2). You may be familiar with Pullman as the novelist on which the film The Golden Compass is based, a 2007 fantasy-adventure film based on the first novel in the trilogy, Northern Lights.

In the trilogy, Pullman’s daemon, pronounced like the Judeo-Christian word “demon”, is anything but a demon in the conventional sense of an evil spirit. In fact, it may be that Philip Pullman chose to spell his spirit guides in Lyra’s world in a way that would make those imbued in the western tradition initially react with scepticism.

As Pullman’s character Will explains when he first encounters Lyra and Pan, her daemon, “In my world demon means … it means devil, something evil”. Yet readers soon find out that a character’s daemon is rather like a guardian angel, looking out for his or her human companion and providing security in times of loneliness.

In fact, when Will is confronted by Lyra’s use of the words “we” and “us” to refer to herself and Pan, he is overwhelmed by a sense of isolation at the realisation that he has no daemon: “Will looked at the two of them, the skinny pale-eyed girl, with her black rat daemon now sitting in her arms, and felt profoundly alone”. Thus, on the simplest level, a daemon in Pullman’s world is an animal companion to each human spirit but, just as Pullman’s work can be analysed on various levels, so can the daemon and its symbolic representations.

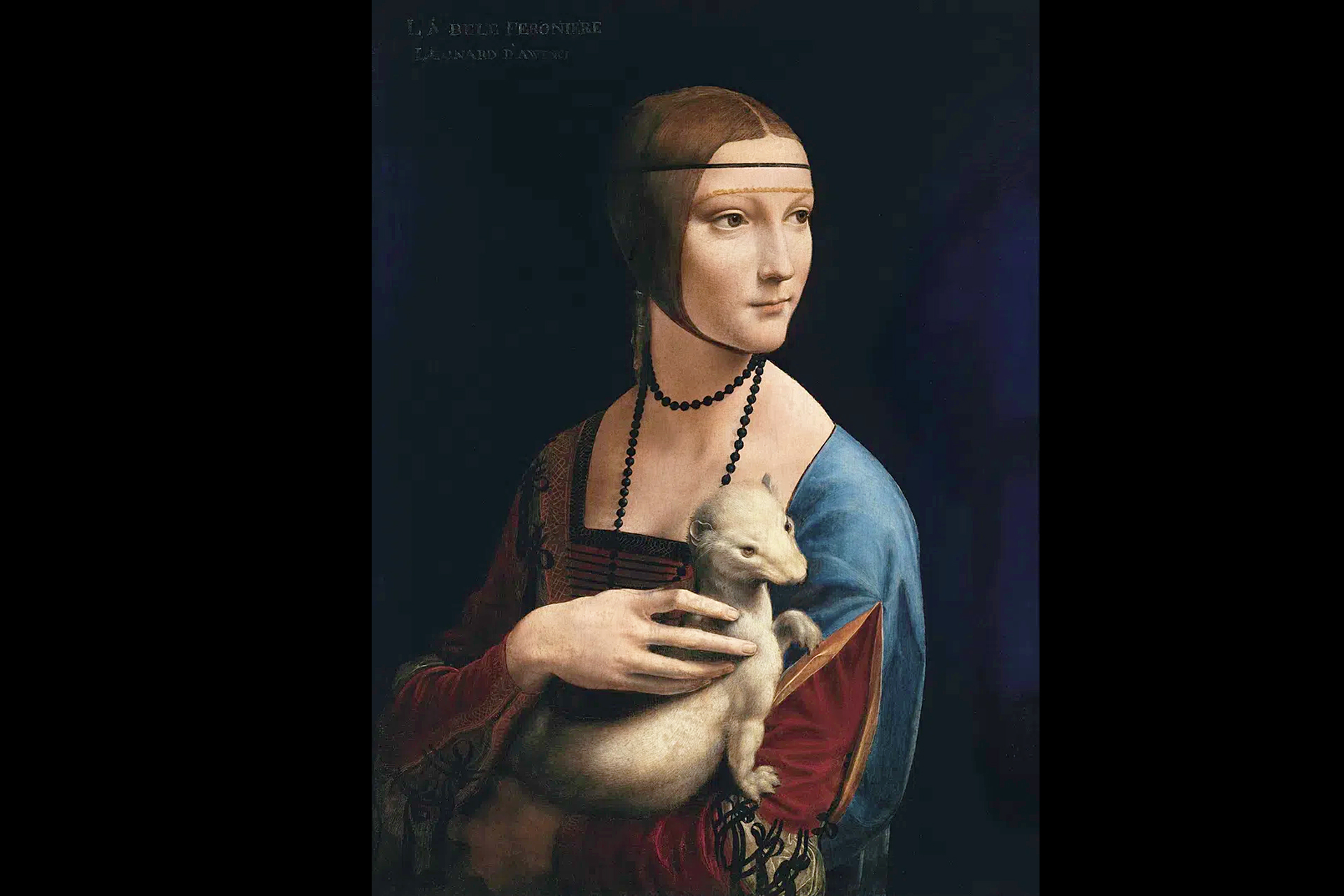

Pullman claims he had no idea where the idea of daemons came from, but further investigation reveals inspiration in the form of a work of art. Once, in Poland, Pullman saw the painting by Leonardo DaVinci of a young girl holding an ermine (reproduced above) and the connection between the two was so evident that he envisioned Lyra and Pantalaimon as a girl and her daemon.

The human-daemon link represents conflicts between internal and external expression. Various passages in Pullman’s trilogy reveal instances when the children (or the adults) behave in one way while daemons betray predominant, yet hidden, emotions.

Modern examples in management thinking

Dr Steve Peters created a mind model which helps him coach and maximise high-level sports performance. Peters is a sports psychiatrist who works with the successful British cycling team and the professional cycling road racing outfit, Team Sky, who have provided the individual winner in two consecutive Tour de France events. He also works for Liverpool Football Club. After the 2012 Olympics, he was appointed by UK Athletics to work with the country’s high-performance athletes.

In his book, The Chimp Paradox, he attempts to illustrate the same inner mental struggle that Richo and Pullman write about. Peters explains how to use our inner chimp for good rather than let it run rampant with its own agenda.

In their joint book, Switch, Chip and Dan Heath ask the question: why is it so hard to make lasting changes in our companies, in our communities and in our own lives? As all our authors have identified, the primary obstacle is a conflict that’s built into our brains. The rational mind wants a great beach body; the emotional mind wants that piece of cake. The rational mind wants to change something at work; the emotional mind loves the comfort of the existing routine. This tension can doom an effort to change but, if it is overcome, change can come quickly.

Organic or spiritual?

For any of us with a mystical, or spiritual, sense, it may be that our daemon is not just a matter of wiring in our brains or something that is simply an individual phenomenon but a daemon, in this sense, could be a conscience with a spiritual dimension. I will leave that philosophical debate for others but, bear in mind, that when I refer to a daemon, it could be purely psychological, or a more spiritual phenomenon, depending on your beliefs.

Practical repercussions

So how do we access our daemon and how does that help us in a practical sense? Most of us would admit that we have had conversations with an internal self and we are well aware that we make decisions and judgements that have little to do with conscious thought.

In Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, he describes the working of the adaptive unconscious, the gut reaction; mental processes that work rapidly and automatically from relatively little information. Gladwell considers both the strengths of the adaptive unconscious, for example in professional judgment and its pitfalls such as stereotyping people and jumping to early, erroneous conclusions.

Debating with our internal “voice” and coming to a decision by balancing conscious and unconscious factors might seem an impossible task. But what is the alternative, to make decisions based on one or the other?

Take someone who wants to lose weight. The conventional approach is to be totally rational about it, to join a diet group and rely on the feedback of losing a pound or two each week to maintain a logical motivation. Your conscious brain endorses a limited calorific diet and tries to follow it.

Their daemon hasn’t been consulted during this decision-making process and, next time the rational dieter passes a fast food outlet, their daemon is saying things like “One Big Mac will not a diet ruin”; “Treat yourself for once.”

I have recently lost two-and-a-half stone in weight so I speak from some experience. I decided to engage my daemon from the start. I gave her a name, Lola, and saw her taking the form, in Pullmanesque-style, of a Bengal cat, a hybrid breed of domestic moggy. Bengals result from crossing a domestic feline with an Asian leopard cat and they are only four generations away from being totally wild.

To start a conversation like this is akin to meditation. In fact, meditation has a number of things in common with it. As I see it, the conscious brain makes some assertions about the sort of target weight needed and what that weight might mean in terms of basic Maslovian factors like self-esteem, sexual attraction, new clothes, success and status at work, more energy – lower-level drives that the subconscious can grasp and thrive on.

These assertions must be regularly-voiced internally, every day if possible. A period of concentration is needed, a quiet moment just after getting up in the morning, for instance. Voicing them out loud helps and ensures that the assertions are stated clearly.

Using an animal form to metaphorically represent your daemon helps, in my view, to hold such imaginary conversations. When the fridge is opened and some calorie-rich snacks present themselves, I would conceive my daemon on my shoulder and, if I were to reach for a block of cheese, I imagine my daemon licking her forefoot vigorously. “Do that, my conscious friend, and you will not be that Übermensch you described to me a month ago.” No, I would not.

My conversation worked: the Übermensch came through. The editors of this blog have even suggested that I am a “shadow” of my former self!

Clear thinking and useful action requires self-knowledge and I am proposing that internal conversations to discover why we do some things, react in certain ways and make gut reaction decisions are a key part of self-knowledge. You may think I went too far in adopting a Pullman daemon but this metaphor helps me communicate with parts of my mind that are not easy to understand.

I would love to hear about your experiences. What would you change, how would you go about thinking about and deciding on change? Would it be useful for you to think in terms of a daemon, to personify your daemon and how would you decide on its animal form?

Jeremy Dent – Guest Contributor

References

Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking: Malcolm Gladwell. Blink is a book about how we think without thinking, about choices that seem to be made in an instant-in the blink of an eye –that actually aren’t as simple as they seem.

Shadow Dance: Liberating the Power and Creativity of Your Dark Side: David Richo. Our “shadow” is the collection of negative or undesirable traits we keep hidden—the things we don’t like about ourselves or are afraid to admit: egotist, non-“PC” proclivities, forbidden sexual desires. But it also includes our positive, untapped potential—qualities we may admire in others but disavow in ourselves.

His Dark Materials: Philip Pullman. Wikipedia entry.

The Chimp Paradox: The Mind Management Program to Help You Achieve Success, Confidence, and Happiness: Dr Steve Peters.

Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard: Chip and Dan Heath.